Talk Overview

Ben Barres gives advice on how to pick a graduate advisor. He strongly suggests picking an advisor who is not only a good scientist, but also a good mentor. In this talk, he describes a mentor’s qualities and attributes, and gives suggestions on how to identify an advisor who will be a good mentor.

Speaker Bio

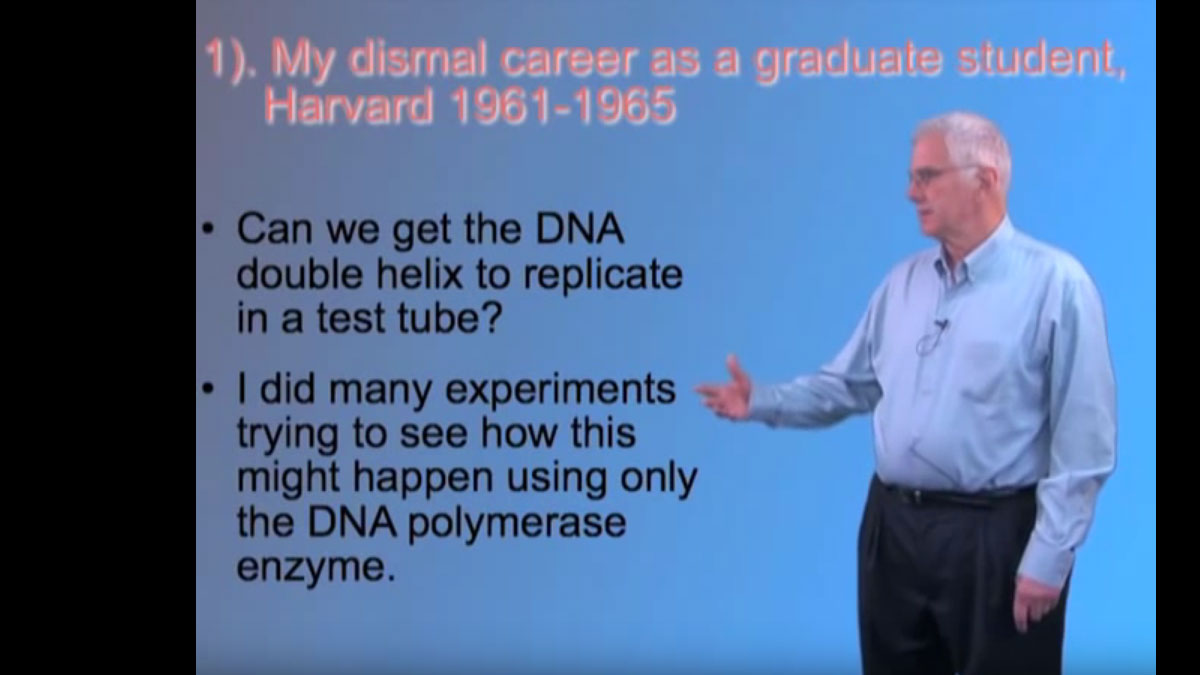

Ben Barres

Dr. Ben Barres is a professor at the Neuroscience department at Stanford School of Medicine. Barres earned his BA in biology from MIT, and completed a medical degree at Dartmouth Medical School. He continued his medical training as a neuroscience resident at Cornell University, completed his PhD in Neuroscience at Harvard Medical School, and joined… Continue Reading

Leave a Reply