Talk Overview

Shirley Tilghman talks about a Malthusian dilemma in biomedical research. For almost a decade, available research dollars has stayed the same or decreased, while the number of awarded PhDs has risen rapidly. This has resulted in an increase in training times for graduate students and post-docs – a phenomenon she calls a “bulging pipeline.” Tilghman presents several concrete solutions to begin to address the impending unsustainability of the biomedical workforce and improve the Malthusian dilemma.

Speaker Bio

Shirley Tilghman

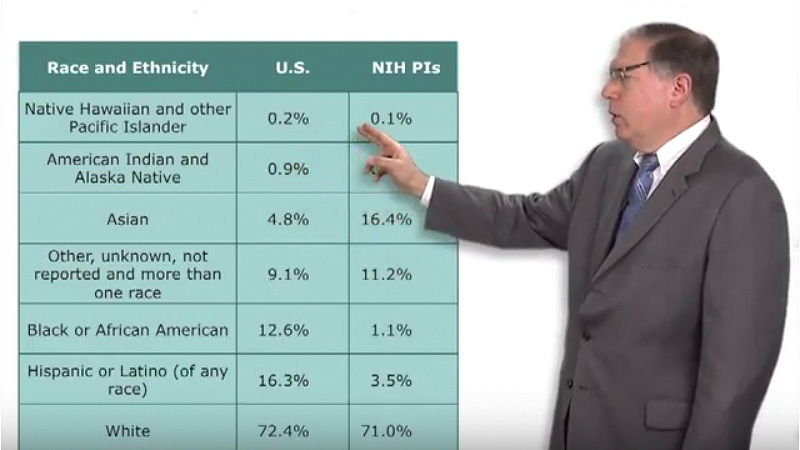

Shirley Tilghman is the President Emerita and Professor of Molecular Biology at Princeton University. Dr. Tilghman is a strong visionary and leader in academic research and higher-level education. As President of Princeton University for 13 years (2001-2013), she implemented policies and initiatives that supported better training of Princeton students and increased diversity in the faculty… Continue Reading

Leave a Reply